Taking a look back at what web3 has accomplished since 2018, there are a lot of things to be proud of. Defi took off like a rocket, bringing new entrants to the market, DAOs gaining traction, and NFTs becoming a household term. But looking into the future of blockchains and web3, there are a few clouds. MEV (Maximum Extractable Value) is rapidly becoming an existential problem.

Price and market information improves liquidity, but when the entities that find MEV also finalize transactions, it leads to a centralizing effect. Although MEV threatens cryptoeconomic protocols’ decentralization, there are ways to address them.

Here we talk about what MEV looks like in TradFi, the various players in the MEV supply chain, and what the future holds for it. We also give you a fun example of an MEV attack and a bit of karma for the harvester.

MEV in Traditional Finance

High Frequency Trading

Flash Boys, a book by Michael Lewis about high frequency trading (HFT), documents trading firms that created a method to front-run orders placed by investors. HFT existed in some form since the 1930’s when the telegraph was used to communicate positions across exchanges, but didn’t gain momentum until 1983 when the NASDAQ introduced purely electronic trading. HFT as we know it today was developed and popularized in the mid 2000’s as the markets began to modernize. As a result, cross market trading began to take off.

Today, small arbitrage opportunities occur all the time in traditional finance. These opportunities arise in milliseconds and are imperceptible to humans, but are perceptible by computers. One company, called Spread Networks, spent $300 million constructing a fiber optic cable 827 miles long from Chicago to the Nasdaq data center in New Jersey.

Before the project, trades on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange were transmitted in just 17 milliseconds. After the project, transmission time was 13 milliseconds. Contrast that to the average human blink, which lasts 100 milliseconds.

This 4 millisecond difference, $300 million for a 23.5% speed increase, allows HFT firms to see orders to buy a stock, buy the stock before the orders can be executed, and sell the stock to the original purchaser for a slightly higher price.

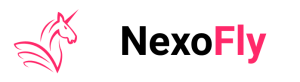

Everyday retail investors purchasing stock don’t have access to these systems, and are constantly getting front-run by such HFT firms. These trading firms profit off of retail investors and earn billions of dollars a year. According to the Financial Times, HFT accounted for 65% of US stock market volume in 2008. Some estimate HFT accounted for as much as 78% of total trading volume in 2009.

Arbitrage increases liquidity across markets and closes the difference between bid and ask spreads—leading to better prices—and HFT firms skim the difference.

Colocation

Banks were trying to make their systems as fast as possible, even by putting their servers inside stock exchange buildings in a strategy called colocation.

One HFT firm was able to secure a spot “[…] a few feet nearer to an exchange computer that had previously been occupied by machines owned by Toys ‘R’ Us.” The firm got a slight advantage of just inches, but this is a competition for microseconds and nanoseconds. This advantage increased the firm’s profits, but if competitors knew about the computers they would respond in kind.

In fact, the firm with the Toys ‘R’ Us computers was so paranoid about hiding this slight advantage, the HFT firm insisted the Toys ‘R Us logo was not changed after they had moved in.

Brad Katsuyama was the global head of electronic sales and trading at the Royal Bank of Canada when noticed that large trades were being taken advantage of by scalpers and resulted in worse prices. After digging deeper, he discovered these fiber optic cables and colocation agreements allowed HFT firms to take advantage of retail traders.

As a result, he founded IEX which is an exchange designed to be a fairer stock trading venue by creating an alternative system. Exchanges like IEX are trying to reduce the effects of HFTs through design. IEX:

- Has published its order matching rules

- Refuses to pay for order flow

- Charges fixed fees on large orders and a flat percentage rate on small ones.

- Avoids colocation

- Ensures market pricing data arrives at external points of presence (internet exchange points along your packet’s path) simultaneously.

IEX has even created a “Magic Shoebox”. Designed to slow down traffic coming in and out of the exchange.

This box contains 61 km of fiber optic cable that’s designed to add a 350 microsecond delay. Essentially, creating a speed bump for all network traffic.

IEX is an alternative trading system (ATSs). These ATSs exist outside of traditional securities markets. They are regulated, but many have problems with insider trading and predatory behaviors especially when trades are anonymous and have no specific order information before trades occur. These anonymous ATSs are called Dark Pools.

Dark Pools

Dark pools are private exchanges for trading securities. These exchanges are pools of liquidity not accessible by the investing public hence the name dark pool. They allow hedge funds and institutional investors to make privately negotiated trades, called “block trades”.

Some institutions use these pools to avoid large price impacts and can be broken up into smaller orders executed across various exchanges to hide trading activity (see more).

Dark pools are categorized as “Alternative Trading Systems (ATSs)” by the SEC. Dark Pools allow large entities to trade anonymously, without revealing the order price nor size to other dark pool participants. These dark pools exclude HFT firms, providing a refuge from front-running.

The problem for Dark Pools is attracting sufficient liquidity in order to execute trades at reasonable prices. In an effort to increase liquidity Dark Pools give their own proprietary trading desks access to the markets.

Dark pools move the information from large national exchanges to private exchanges, but the same arbitrage opportunities exist. This information advantage is too profitable to ignore because several dark pool operators have given their own trading desks information to improve their trades, front-running their customers. One dark pool operator’s compliance department warned them that this was illegal, and they did it anyway.

Another dark pool operator (Pipeline Trading Systems) was caught operating an undisclosed proprietary trading desk (division of the company that places trades) which composed the overwhelming majority of volume within the dark pool. Not only did their “Affiliates”—aka the Pipeline Trading desk—get information about trades, they also got better access to the system (colocation) and information about the Pipeline’s order-matching engine (the system’s rules) so they could more effectively front-run other dark pool subscribers.

Still yet another large dark pool operator gave HFT funds access to their pools with special order types, allowing them to get an unfair advantage over regular subscribers. They even let some preferred subscribers avoid trading against the HFT funds. The dark pool let HFT coyotes into the henhouse, armed these coyotes with forks and knives, and created a “VIP” section where special hens could order omelets and watch the mayhem below.

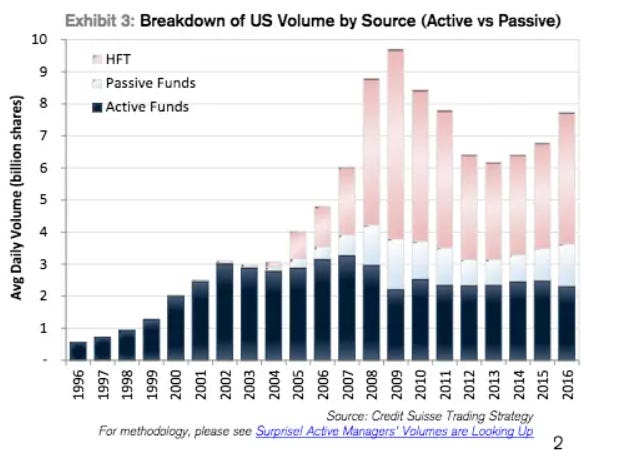

Payment for Order Flow

Payment for order flow is another way to capitalize on this price information. Market makers will pay Stockbrokers to route users’ trades to market makers for fulfillment. Robinhood made huge waves as one of the first broker-dealers to offer free trades and zero fees on account maintenance or any fund transfers. How do they afford to do this? Famously, market maker Citadel Securities buys Robinhood’s order flow for $2.6 billion a year.

Bernie Madoff, infamous for running the largest ponzi scheme in history, said this of payment for order flow:

“[…] It was characterized as this bribe and kickback and something sinister, which was very easy to do. But if your girlfriend goes to buy stockings at a supermarket, the racks that display those stockings are usually paid for by the company that manufactured the stockings. Order flow is an issue that attracted a lot of attention but is grossly overrated.” -Bernie Madoff

Broker-dealers are obligated by law to provide a “best execution” price—no worse than the National Best Bid and Offer (NBBO)—to their customers, but these prices notoriously do not provide the level of information needed for customers to verify them. NBBO prices often go unrecorded making it extremely difficult to determine whether traders got the right price or not.

Even if the prices are recorded, HFTs can take advantage of the latency between the NBBO’s calculation time and its publication. Because HFTs can access market information (prices) faster than the NBBO price can be published, HFTs will pre-calculate future NBBOs, front-run trades, and pocket a small but assured profit. Payment for order flow (PFOF) allows brokerages to share in some of these profits.

The SEC has said about PFOF:

“While the fierce competition brought on by increased multiple-listing produced immediate economic benefits to investors in the form of narrower quotes and effective spreads, by some measures these improvements have been muted with the spread of payment for order flow and internalization.”

MEV in Blockchains

All of these TradFi examples of arbitrage come from one thing: Having access to information. Intuitively, buying something and selling it for more than you bought it for is not a new concept. It’s not always bad either. In fact, arbitrage is a crucial part of these systems because it improves market efficiency.

It’s seen in traditional finance and in Amazon retailers. Amazon reselling has gained huge traction among the Zoomer cohort. Often purchasing products in stores, then marking up the prices and selling them on Amazon.

But crypto is speed-running the history of finance. MakerDAO created the first decentralized lending project in 2014, Uniswap launched in 2018, and Compound set web3 on fire with yield farming in 2020. With DeFi comes opportunity.

There’s a new kind of arbitrage in finance: Maximum Extractable Value (MEV). Formerly referred to as Miner Extractable Value, MEV includes DEX arbitrage, liquidations, and NFT sniping are possible through crypto-economic protocols like Ethereum and it is very valuable. There are bots constantly searching for these opportunities throughout the mempool, but ultimately, the entity that has final control over these arbitrage opportunities is the block producer.

In proof of work systems, miners are the block producers, and in proof of stake systems, stakers are the block producers. Because these entities produce the last set of transactions to finalize, they can add, remove, or replace transactions as they see fit without intervention from others. Only block producers can guarantee the execution of MEV transactions, so if they find an arbitrage opportunity, they can capture it. In web3, block producers have “god mode”.

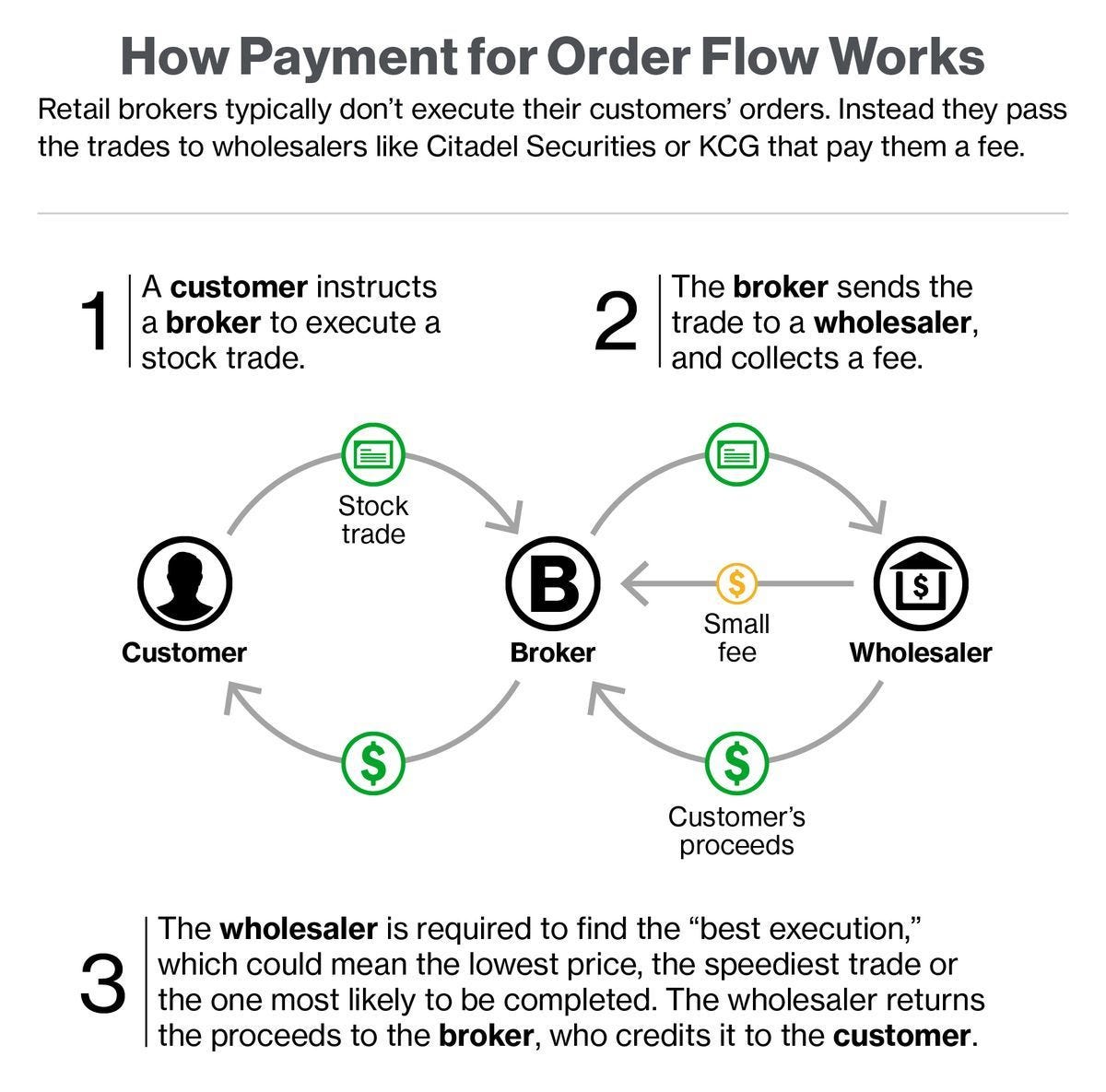

The MEV Supply Chain

The MEV Supply Chain describes the chain of activity which helps users transform intentions into finalized state transitions in the presence of MEV.

Stephane Gosselin

The MEV supply chain plays an essential role in the MEV landscape. Regardless of MEV mitigation techniques or ordering rules of transactions, the MEV supply chain exists in all blockchains. The players of the supply chain might look different on each blockchain, but the interaction between them is crucial because poor design can lead to a dystopian result.

Who are the MEV Supply Chain players, and what are their roles?

User

The start of the chain is always the user: anyone with the intention to interact with the chain, be it buying an NFT, swapping USDC for WETH on Uniswap, or taking out a loan on Aave.

Wallet / Application

Wallets are the interface connecting users to the blockchain. The Application Layer groups together dApp UIs and Smart Contract Protocols. Components work together to execute user intent.

On this layer, developers can make decisions on behalf of their users on how to deal with MEV. For example, a critical decision for wallets is whether the transactions are submitted to the public mempool or directly to a builder privately. The difference is that bots monitor the public mempools to identify MEV opportunities, as it’s where pending transactions usually reside. Private transactions fly under the radar of these bots because they skip the mempool and are directly submitted to a block builder. They protect users from being attacked directly by bots but don’t mitigate MEV, as the MEV extraction opportunity just gets pushed to the next block.

Searchers

Searchers are users that try to identify MEV opportunities by running complex algorithms, sorting through on-chain data and transaction pools, and operating bots. Their name comes from their “searching opportunities” task – hence the name searcher.

Even though their main goal is to extract the most profit for themselves, they play a vital part in the DeFi ecosystem by balancing markets and ensuring fast liquidations. But in dysfunctional MEV supply chains, searchers could extract a disproportionate amount compared to what they provide, leading to an MEV dystopia.

Builder

Builders aggregate transactions to construct a block.

Before the Merge, the role of building blocks and proposing them was handled by miners. After the Merge, the concept of Proposer Builder Separation (PBS) was put forth, allowing independent parties to fulfill each task. This enables block proposers to become lighter clients in the future to strengthen decentralization, as building blocks can be computationally heavy. In the current state, block proposers can still build blocks themselves, but once PBS gets implemented into the core Ethereum protocol—called enshrined PBS—this will no longer be possible, and the roles will be separated.

In Layers 2s, the sequencers play the builder role as they construct rollup payloads to submit to Layer 1.

Validator

Validators, aka Block Proposers, have consensus duties. They are the ones who propose, validate, and finalize blocks. As mentioned, they also had the role of building blocks and will continue to.

Relayers

Relayers are a temporary entity between proposers and builders. The problem that led to the need for relayers is that proposers can still build their blocks. Hence, when selecting a block from a builder, the proposer could reconstruct it and capture all MEV for themselves, cutting out the builder from the deal.

In short, Relayers prevent proposers from stealing MEV from builders.

The Relay MEV-Boost, built by Flashbots, takes the builders’ blocks and verifies they are legitimate. They then present the blocks to the proposers by only showing the profitability of the block, not revealing the content. The proposer then picks the most profitable block, commits to proposing it, and the relayer sends the block content over so the proposer can submit it.

With enshrined PBS, Relayers will become obsolete as Block Proposers will not be able to build the blocks for themselves. Until then, this trusted party enables the cooperation of builders and proposers off-chain.

Example MEV Attacks

Searchers have a variety of opportunities to extract MEV. There are two broad categories: Short-Tail (ST) MEV and Long-Tail (LT) MEV. ST MEV occurs frequently and is highly competitive. LT MEV, on the other hand, is a one-time opportunity like a DAO proposal that changes a protocol’s parameters and creates the MEV as a result. We will look at the two most common ST MEV strategies – Arbitrage and Liquidations. We will also discover three techniques for how searchers place their transactions in a block to extract MEV.

Arbitrage

“Arbitrage is the simultaneous purchase and sale of the same asset in different markets in order to profit from differences in the asset’s listed price.” – MEV Wiki.

Arbitrage exists in all markets; in crypto it’s the price difference between protocols where tokens can be swapped. This can be a Decentralized Exchange (DEX) like Uniswap, or protocols where you can mint one token for another (e.g. wrap ETH to stETH). The constant flow of transactions by users constantly causes shifts in prices that searchers can expose.

Arbitrage can come in many forms and sizes; essentially, it always takes advantage of price differences.

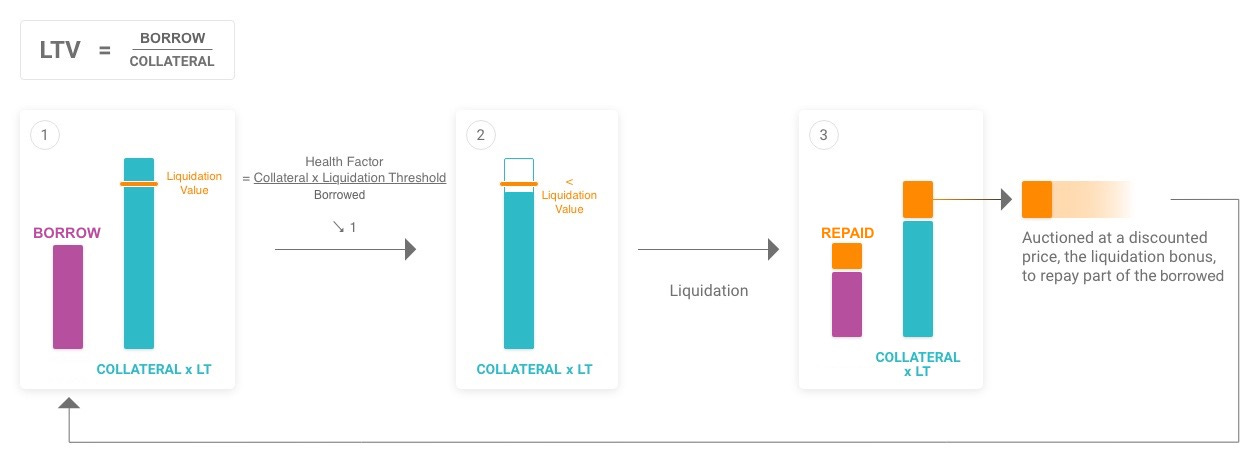

Liquidations

When taking out a loan on Aave, you need to supply collateral that can be taken from you if you cannot repay the loan. In DeFi, the loan collateral rate is very high. For example, if you don’t want to sell your ETH because you think it will go up but need $1000 USDC, you go to Aave and supply $2000 worth of ETH to take out the USDC. Unlucky you, you did this before the bear market started, and now your provided collateral is only worth $1200. This puts your collateral below the allowed threshold, and you can be liquidated by anyone.

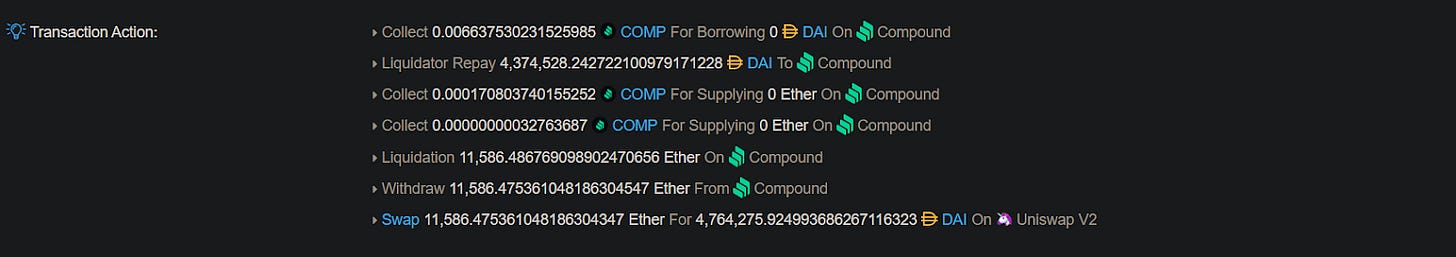

This liquidation is often executed by searchers constantly watching all positions, trying to be the first to trigger a liquidation. Liquidations can often be quite profitable as searchers receive the hefty liquidation fee a borrower pays. Take this transaction, for example. It made $2.2 Million in Gross Profit by liquidating a loan on Compound.

From the Front to the Back to the Sandwich

Front- and Back-Running is not an MEV strategy like arbitraging; it describes how the searchers place the transactions in the block.

Back Running

Back running means the searcher places the transaction right after the one that exposes an MEV opportunity. For example, suppose someone swaps a large amount of USDC for ETH on Uniswap. In that case, it will cause a price shift between DEXs, allowing a searcher to place their transaction afterward to capture the arbitrage opportunity. Back running is harmless as it does not damage other network participants.

Front running

Front running means placing the transaction right before the targeted transactions. A widespread use case is generalized front-running bots that snipe profitable transactions of other users or bots. This works by monitoring pending transactions, copying profitable ones, and submitting them with a higher gas fee to ensure sooner inclusion. This approach became less effective with the introduction of Flashbots, as bots can now skip the mempool to fly under the radar of front-running bots.

Sandwiching

Sandwiching is front- and back-running combined. Their structure is “Searcher TX – User TX – Searcher TX,” hence the name Sandwich.

An example of a more notorious attack is sandwich attacking a DEX swap made by a user. Due to the self-balancing nature of DEXs, the price of the bought asset increases after the swap—the greater the exchanged amount, the greater the price increases. Sandwich traders take advantage of this by purchasing an asset for cheap before a large trade passes through and selling the asset afterward for a higher price. This increases the slippage of the targeted user leading to a loss.

A Peek into the Future of MEV

MEV is the value that comes from information about economic activity. MEV can also be reframed as the value of information. MEV comes from having access to this information before anyone else or the ability to interact with it in privileged ways and benefit from it. MEV allows DeFi to function by improving market efficiency.

Transaction ordering is the source of MEV’s power. Block producing entities have the ability to add, remove, or reorder transactions to extract value that the system wasn’t designed to emit.

Front-running, back-running, and sandwich attacks are some examples of arbitrage techniques that target DEXs. These attacks are quickly becoming more sophisticated, including: NFT sniping, liquidations, and cross-domain arbitrage.

In traditional finance, order flow is the equivalent of “MEV”. High frequency trading is one example of MEV extraction. HFT firms can front-run, back-run, and sandwich attack user transactions that are routed through them. These firms invest heavily into reducing latency in order to capture this value, and co-location has become a lucrative business for exchanges, which charge HFT firms millions of dollars for the privilege of “low latency access.”

The Dark Side of MEV

Bot operators are constantly looking for opportunities, this is bad for users when they make mistakes like accidentally setting high slippage limits.

MEV can be extracted via:

- Spam War: In this scenario, transactions are ordered randomly, which incentivizes bots to send thousands of transactions in order to capture the opportunity. Taking up a ton of block space, memory & compute resources, and crowding out typical use cases.

- Latency War: Ordered transactions, first in first out (FIFO). Block builders (MEV searchers) are then incentivized to quickly send transactions to block producers. The closest block builders will be able to buy the block space fastest, causing a latency war. The most dominant block producers sell access to block builders which centralizes validators and block production.

- Auction: Block construction is outsourced to 3rd parties, and block builders compete on price rather than latency. Efficient markets determine the dynamic between block production and MEV searchers. Flashbots is one such auction solution.

MEV Dystopia vs MEV Utopia

Dystopia

Colocation services create gatekeepers in block builders and MEV capturers. In this economic design, block builders and block proposers will combine forces, oversee transactions, and capture MEV. This has a centralizing effect because the more profitable this entity is, the more capital they can acquire to capture block rewards through mining or validating.

Eventually, this entity will create more validators and become so powerful that they can determine protocol rules and soft-fork the chain. Centralization like this is not Byzantine Fault tolerant and defeats the credible neutrality of blockchains.

This future will resemble traditional financial:

- Centralized actors

- Permissioned broker-dealers

- Government induced monopolies

Utopia

Transactions are permissionless and censorship resistant with transparency of the MEV supply chain. The value that each actor extracts is visible and apparent to users.

Competition is used to determine market prices through proposer builder separation (more later), and block producers are extracting value in proportion to the amount of stake that they have in the network.

Flashbots and the Current State of MEV

Flashbots was created to prevent exclusive access to hash rate.

The “MEV Dystopia” describes a combined entity (composed of node operators and MEV searchers) that extracts value from transactions, splitting the profits. This creates a private market for block space and has a centralizing effect on block space. Actors that get these extra profits can reinvest them into:

- More Nodes

- Better MEV strategies

Alternatively, Flashbots creates a market for block producers to sell their block space for the greatest profit. Flashbots released MEV-Geth which is client software that allows Ethereum miners to accept transaction bundles from 3rd party block operators and include them into their block.

Post-Merge, Flashbots now lets validators use MEV-Boost to maximize their staking rewards by selling block space to block builders.

Chains without an MEV solution face problems like deep [reorgs](https://cointelegraph.com/explained/what-is-chain-reorganization-in-blockchain-technology#:~:text=A blockchain reorganization attack refers,security risk called chain organization.), spam, and concentrated block production.

If one party has enough money to buy another part of the MEV supply chain, they will. So the only way to protect the decentralization of the entire stack is to create sufficient competition at all layers.

MEV-Boost

MEV-Boost is a sidecar solution for validators to sell their block space, without being tied to a particular client. MEV-Boost is feature complete and in the testing stage.

The goal of MEV-Boost was to create a permissionless system where any validator could benefit from MEV.

In Ethereum POW, miners were incentivized to run MEV-Geth clients in order to capture the additional rewards from MEV. This led a large majority (90%) of miners to run the software, reducing client diversity. The majority of Ethereum POW nodes are Geth nodes. MEV-Boost works with “any Ethereum consensus client” promoting client diversity; Prysm, Lighthouse, Teku, etc.

Estimates from Flashbots say that 60% of total validator rewards will come from MEV.

Proposer-Builder Separation (PBS)

Block producers have a complete view of the content of MEV bundles, which gives them the option to front-run, censor, or otherwise extract value from them. Searchers must be careful regarding to whom they send these bundles.

Any average validator could take this value for themselves, leading MEV searchers to exit the auction system. Then, a similar market dynamic outlined in the MEV dystopia will materialize: MEV searchers and validators combine resources to outcompete other searchers and validators.

The MEV solution outlined using MEV-Geth doesn’t scale with the number of validators. The solution is to separate the responsibilities of validators into two roles: block “proposers” and block “builders”.

Block builders will accept bundles from MEV searchers, build entire blocks from these bundles, encrypt the blocks, and then send the blocks to validators. Validators cannot see the contents of the block. All they have to do is determine how much value the block contains and pick the block with the highest value.

Create a block builder role where they assemble bundles from MEV searchers into blocks who send these blocks to the block proposers (validators). Block builders bid on block space and validators will choose the block they want to add based on these bids (or among other factors).

⚠️ Note: There could still be centralization at the builder level.

This allows individual stakers to benefit from MEV. This shifts centralization to the ”Builder” layer, but it’s better to have centralization at that level than at the validator level. In any case, it gives us another opportunity to address the power law dynamics of MEV.

Enshrined PBS

Relayers

With MEV-Boost, “Relayers” receive blocks from block builders and submit them to validators for inclusion. Once Ethereum introduces PBS at the protocol level, the need for relayers goes away.

With most centralization risks comes censorship risks, however relayers don’t have an incentive to censor transactions. They leave money on the table if they do censor transactions. It should be noted that relayers can be coerced into transaction censorship by governments. Ideally, there is enough relayer diversity such that relayers not in that nation state can pick up those transactions. In turn, these relayers would be more profitable than the censoring ones and the subsequent validators.

In any case, enshrined PBS has a solution: crLists.

crLists

Enshrined PBS uses crLists to replace relayers. This scheme has block proposers create a list of transactions called the crList that have the correct nonce, sufficient balance, and sufficient priority fee and max fee.

Conclusion

At some level, centralization is going to be a force to contend with at all parts of the stack. Centralization is something of a law of the internet at this point. Anything with returns to scale and network effects will create natural monopolies.

The best we can do is introduce competition in order to create the best service, but if the best service is a centralized one, is that what we want? At some level, that kind of power and control can lead to censorship, which is what crypto stands against.

The Byzantine Generals Problem is a way to determine shared truth even if there are malicious actors in the game, and to prevent transaction censorship. At some level, decentralization is an insurance policy. We don’t necessarily need censorship resistance at all layers of the stack.

The need for censorship resistance on Instagram may not be as important as financial transactions.

Via this site